2. April 2023

Swiss Peaks 360, Base Period Reviewed

Two weeks left in what I called the base period in my preparation for this year’s edition of the Swiss Peaks 360 foot race. Time to look back, subjectively and objectively, assess progress (or the lack thereof), and thus set the foundation for creating a more detailed plan for the upcoming training period.

Two weeks left in what I called the base period in my preparation for this year’s edition of the Swiss Peaks 360 foot race. Time to look back, subjectively and objectively, assess progress (or the lack thereof), and thus set the foundation for creating a more detailed plan for the upcoming training period.

What I said would happen

In my previous article Swiss Peaks 360, Prepping for the Next Edition, I roughly laid out the training periodization I had in mind for the 2023 edition. What I refer to as “base period” essentially refers to building general endurance and general speed as described by Steve Magness in “The Science of Running” [1], quite obviously through the lens of my own interpretation.

What I said in February would happen in the base period…

In the “base period”, I am working on general endurance (think: long and slow) and general speed (think: steep and fast), as well as on my weaknesses (downhill technique, running economy).

as well as

[…] in the remaining weeks of February and in March, I will focus on seeking out technical downhill trails; I will incorporate hill sprints, strides, drills, track training, and some intervals; even if that means dialing down on distance and long runs.

With respect to general endurance, things have gone according to plan. Work towards general speed fell a bit short compared to expectations. Whilst I invested into downhill technique and running economy, I can hardly claim I put a lot of focus on these two aspects. But hey, this is part of what actually happened.

What actually happened

So, what did actually happen? Let’s review the two aspects (1) general endurance, (2) general speed, as well as (3) weaknesses (running economy, downhill technique), and finally, (4) strength training and (5) recovery.

General endurance

For general endurance, things went rather well. Such endurance is built by training long, slow, and frequently: volume is important. Over the past 8 weeks, I covered a distance of ~50k, climbed ~1.6k, and spent ~6h running per week. Averages don’t tell the whole story, but it certainly meant that I showed up for the training sessions.

Zooming out a little bit, in 2023 Q1, I ran for a distance of 601k with 17k elevation gain, which took ~69h in total. In comparison, when I trained for the very same footrace in 2022 Q1, I covered 618k with 15k elevation gain in ~66h. Assuming that climbing 1k is approximately equivalent to running an additional 10k, the volume is thus pretty similar compared to last year. Subjectively, I also feel to be in a good place.

Qualitatively, I am happy that I did not get injured, and I believe this is not a pure accident. I progressively loaded more mechanical stress on the body (the musculoskeletal system) before trying to load the metabolism. That requires patience, patience in keeping intensity down, patience in ramping up the training load to levels that I knew I can eventually handle because I had done so at some points during the previous season. As pointed out in Besonderheiten der Trainingsplanung im Trailrunning, I cannot really rely on any (additional) feedback from training tools about the mechanical stress placed on the body. It’s perception that counts, and being principled about progressively getting the musculoskeletal system used to higher volumes at low intensity, as well as bouts of higher intensity.

In January, I spontaneously signed up for the Arosa Weisshorn Trail race in the snow. Due to weather conditions, the organisers had to shuffle participants into the parallel Arosa Weisshorn Half Marathon race instead. This race went very well, but I paid a toll in having to take it easier in the week to follow. That’s not exactly base building, but it was great motivation. In March, I sponteneously signed up for a trail running excursion in the Jura mountains: 31km (↑ 1900m). This was probably a training error, as it took me way too long to recover: all whilst I should be building capacity at low intensity, not utilizing whatever aerobic capacity I have early in the season. But again, it was great motivation, and it was a ton of fun, so the judges are still out on this one.

General speed

When it came to general speed, I have mixed feelings about how things went. But then I also have less experience in assessing how things should go in this area.

Why strides? I find them a really awesome tool to remind your brain and body on how to run faster. For the sprinters among us, that sounds weird. But for the folks like me who likely weren’t born sprinters, running fast does not come naturally. Strides are low impact. In the next training sessions, my body seems to remember and it’s easier for me to pick up my pace when it fits into my training scheme.

After having done a few weeks with enough low intensity volume to tolerate the mechanical stress, I did a few interval sessions at VO2max pace on undulating, but not steep terrain. These definitely helped out in picking up some speed, and hopefully set me up for pushing the lactate threshold to a pace above 4:30 min/km in the next period.

What I did very intentionally was to complete three hill sprint sessions with lots of repeats lasting 10-20s up a steep slope, with the idea to teach the brain how to activate existing muscle units (I intend to do a couple more in the next two weeks until I reach six sessions, and then ramp down frequency to maintenance only). Subjectively, these sessions made later uphill sessions at slower pace feel easier. These hill sprints are specific strength training. I will keep them in my toolbox for base periods in future.

Overall, I feel I could do better by taking a more structured and methodical approach when it comes to training for general speed. It is unlikely ideal to just sprinkle in some of it because I know that some is better than none at all. Potential!

Strength training

Strength training came more to my attention during the base period. There is (1) general strength training and (2) specific strength training [4], as laid out in the book section “Strength Training for the Uphill Athlete” by Steve House, Scott Johnston and Kilian Jornet [4]. I also have in mind what Jason Koop has to say on the subject in his “Training Essentials for Ultrarunning” [3]. All of the mentioned experienced athletes and coaches have in common that they don’t advocate strength training for the sake of strength training, instead recommend to ask what purpose strength training serves.

I’m buying into the idea that strength can help preventing injuries even during long sessions on the trails at low intensity: if you misstep, much higher forces apply than usual, so higher strength could help in such situations. Even though utilization remains low for pretty much the whole session.

As for the performance improvement, that’s an area that I am still looking into and have much to learn about. This makes it a bit more difficult to review, without a coach to guide me through. I’m convinced that such sessions have a place in my training, and intend to read more. The aforementioned hill sprints fall into the bucket of specific strength training, intended to improve performance.

In March, I started doing regularly strength training in the gym (with weights or bodyweight). The opportunity to work out with a knowledgeable colleague was too good to miss out on! Of course, these sessions might come at an opportunity cost (like cross-training in general); either by taking an opportunity away to rest (which I had been doing on Thursdays in previous weeks, at least in the mornings), or by taking the opportunity away to do more sports-specific exercise. However, I figured that the strength training might help me complement my training with upper-body strength to become a more well-rounded athlete.

Once I have established the habit (strength training is not something I naturally gravitate towards), and once I understand what strength training aspects might (somewhat, I’m a priori skeptical on this) transfer from gym to trail running, these sessions may start to slightly affect performance, too. Since I am not a professional athlete, I could even live with the fact if these sessions don’t transfer into trail running performance on ultra-long distance events.

The authors of the book “Training for the Uphill Athlete” [4] suggest that upper body strength is often overlooked among trail runners, along with concrete suggestions on how to exercise the upper body in a way that is specific to trail running. On the reading list!

Weaknesses

As I mentioned, I intended to work on one of my weaknesses in the base period: running economy, more specifically through drills to improve running form. Apart from not having put much thought on this, I wonder in hindsight how good of a plan that was anyway. I learnt (again) about running economy being a weakness when doing a performance test (playing Darth Vader on a treadmill); historically, I never had good running form, which was easy to assess when looking at videos or even just pictures of myself running on a track. With all the downhill running, running with backpacks, running on trails, running form might suffer, too.

But how important is running economy for ultramarathon performance? I enjoyed reading Jason Koop’s article on this subject, and particularly also liked the Millet’s [2] diagram on the determinants of performance in ultramarathons. I have put Millet’s paper on my reading list. At the end, I consider radical changes to running form risky (from experience, too), and intend to only occasionally sprinkle in some drills to occasionally bring some bounce into the legs prior to specific workouts.

In retrospect, my intention on doing hill sprints and downhill technique and track sessions were too ambitious. These ideas were competing for the same time slots in my calendar. The call for focusing on hill sprints was the right one, I need to introduce a few track sessions in the coming weeks, and make a new plan for addressing downhill technique in the next period.Recovery

Recovery is an important part of the growth equation [5]. Particularly also for sports. After all, it’s not during the workout where we get stronger, but in the period afterwords where the body (hopefully) adapts to the stressor by supercompensation, leaving us in a better position to handle the same stress the next time. Others will do a better job than me to write about the importance of recovery.

I continued my journey in the past months to put more focus on recovery. It’s easy to track distance covered, the amount of vert accumulated, but totally forget about the recovery aspect of training. Particularly, if you like quantifying things like me. Thus, I started to better quantify some aspects of recovery, both through recording perceived recovery scores, and through measuring parameters such as heart rate variability, which I learnt about from one of Koop’s many podcasts.

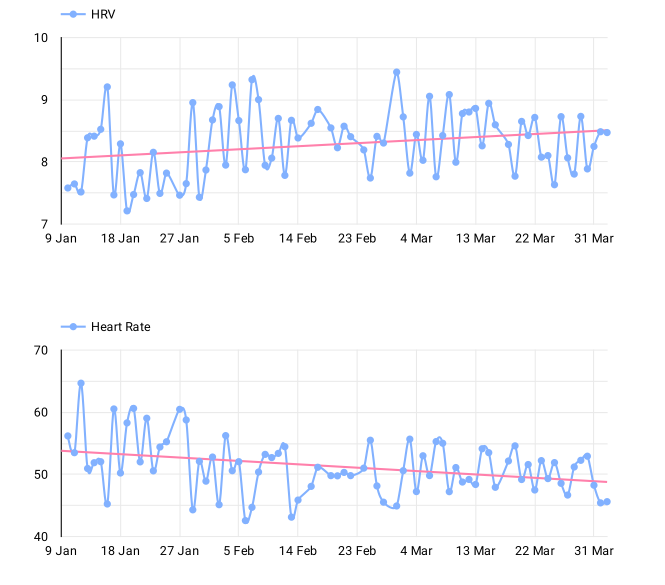

I purchased Marco Altini’s HRV4training app (no affiliation), and have been recording heart rate and heart rate variability first thing in the morning, along with collecting the scores on perceived “mental energy”, “training motivation”, “sleep quality” and so on. After prompting me to think about my current recovery state, and stressors external to training (such as work), the app then also shows me objective feedback.

Above charts show the HRV4Training’s recovery points, which are a transformation of rMSSD as a measure of heart rate variability. The goal is not to target these parameters. Instead, to use the feedback on a day-by-day basis in order to decide whether to adjust my training, in addition to my subjective feeling. I’ll see what I do with it over the next few months.

PS: Of course, there is much more to recovery than quantifying it!

What’s next

The next period is what I called the “support period” in Swiss Peaks 360, Prepping for the Next Edition. I need to figure out what a good weekly schedule is, what key workouts to focus on, review the goals I set, and most importantly, get on with it and show up for the training.

All in all, looking back, I find it very difficult to be my own coach. But it is also highly rewarding, and it keeps me curious to find out how the human body works, and how to make the miracle of training happen. I certainly intend to learn more about the role of strength training in the next few months, all whilst progressing towards getting ready for Swiss Peaks 360 this year, having fun on the trail, alone and with other trail runners.

References

[1] Magness, Steve. 2014. The Science of Running: How to Find Your Limit and Train to Maximize Your Performance. Origin Press.

[2] Millet, G. Y., M. D. Hoffman, and J. B. Morin. 2012. “Sacrificing Economy to Improve Running Performance—a Reality in the Ultramarathon?” Journal of Applied Physiology 113 (3): 507–9.

[3] Koop, Jason. 2016. Training Essentials for Ultrarunning: How to Train Smarter, Race Faster, and Maximize Your Ultramarathon Performance. VeloPress.

[4] House, Steve, Scott Johnston, and Kilian Jornet. 2019. Training for the Uphill Athlete: A Manual for Mountain Runners and Ski Mountaineers. Patagonia Works.

[5] Stulberg, Brad, and Steve Magness. 2017. Peak Performance: Elevate Your Game, Avoid Burnout, and Thrive with the New Science of Success. Rodale.