8. Februar 2026

Controls, Yours Or Mine?

Discovering all kind of difficulties of controlling the aircraft in the GeoFS flight simulator. As well as some remedies, whether in adjustments to software, hardware, or simply through deliberate practice.

Discovering all kind of difficulties of controlling the aircraft in the GeoFS flight simulator. As well as some remedies, whether in adjustments to software, hardware, or simply through deliberate practice.

This article is part of a series on my curiosity-led journey through flight simulation, modeling, navigation & mapping, aviation, control theory, software engineering, and more.

I remember my various attempts with the Microsoft Flight Simulator when I was a child. Typically, they would result in the soon-familiar sound of glass breaking, combined with a broken windscreen covering the laptop screen. Landing seemed near impossible.

Fast forward, say three decades later, and at least at the beginning: not much difference. Except that GeoFS simluator does not produce the same glass-breaking sound effect upon crash-landing the airplane. So what were the difficulties I encountered?

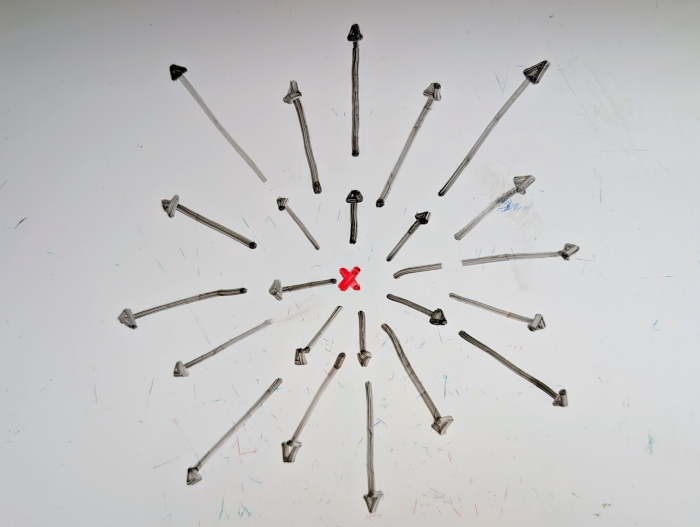

First, when approaching a runway for landing, I found it pretty difficult to keep the airplane aligned with the centerline, particularly from the cockpit view. Without any guidance from a localizer, how to know whether the airplane is too far left or too far on the right? How to know whether it is too high or too low? The following conceptual picture seemed to have help me the most: when flying towards the aiming point (x), that point should not be moving on the screen—that is how I know that I am on the right path. Every other point will move left, right, up or down the screen.

While still a certain distance away from the runway (enough to not run into issues with parallax effect when seated off the airplane’s own centerline), I also found it useful to verify that the left and the right edges of the runway were at the same angle—perspective—when drawing a line from the runway threshold all the way through my own center on where am seated on my office chair (no seat belts).

In hindsight, this may all sound obvious. But it took quite a bit of practice, and a bunch of tips from the Internet (free flying lessons on YouTube) until getting that approximately right, most of the time. However, I was not there yet either. There were at least two more major obstacles between me and a successful landing in the flight simulator.

It is not enough for me to know whether the plan is too far left or too far right, or too high or too low. I also need to correct any lateral or vertical deviation on the approach. Easier said than done. Most of the time, it didn’t really work, and the plane was staying neither on the extended centerline, nor on a constant glide slope.

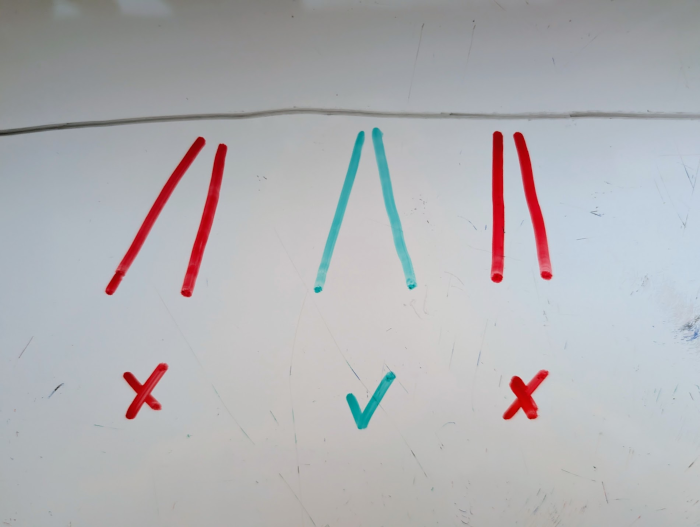

Hypothesis? Overcorrection. This still happened even after I believed that I removed my tendency to overcorrect. At this time, I still used the keyboard to control pitch, roll, yaw, and thrust. New hypothesis? The keyboard only offers coarse-grained control: click the left arrow on the keyboard once, and the plane banks further to the left than needed. Click right, and the plane banks further to the right than needed. This leads to oscillation.

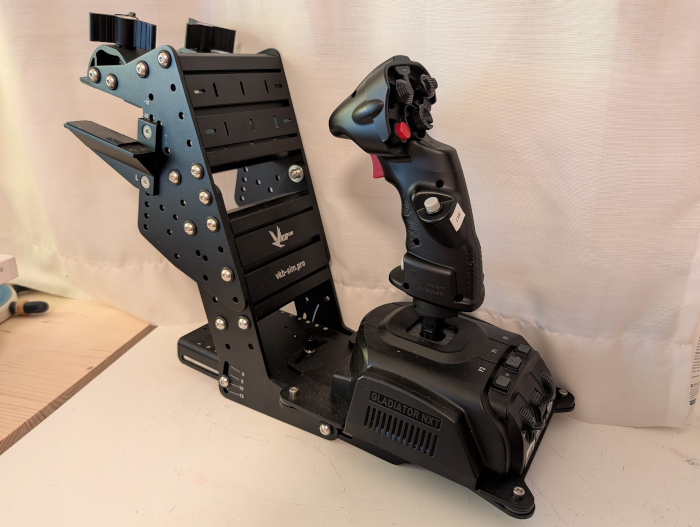

As a software engineer, I tried to solve that problem […] by buying some hardware. A joystick has much higher resolution, and alas, it helped with keeping the plane on the extended centerline. Somewhat.

However, the joystick alone was not sufficient to keep the plane from bouncing on the runway. Lack of practice? Or not enough gadgets? Same problem, likely. The keyboard only allowed to set the throttle to positions 0-9. I figured that was not enough to carefully control airspeed. The flying instructors of the Internet also agreed: controlling airspeed is a key ingredient to a successful landing. Thus, I purchased a throttle quadrant, as well as a rudder pedal. Indeed, having a higher-resolution throttle lever helped in gently reducing the thrust to idle shortly before touchdown.

Done? No, not yet. During slow flight—whose importance, again, I learned from the flying instructors of the Internet—the controls felt too sensitive. Particularly during take-off with moderate crosswind, it was near impossible to keep the plane on the runway with the pedals: no pedals and it would veer off in one direction. Give some pedal, and it would swerve too far the opposite direction.

GeoFS offers to control the sensitivity, but it only offers a single knob for calibration: there never seemed to be the right setting for all phases of flight. The calibration software for VKBsim controllers might have more options to configure the axes of joystick and pedal but it only runs on Windows. More hardware does not help. More practice does not help. What now?

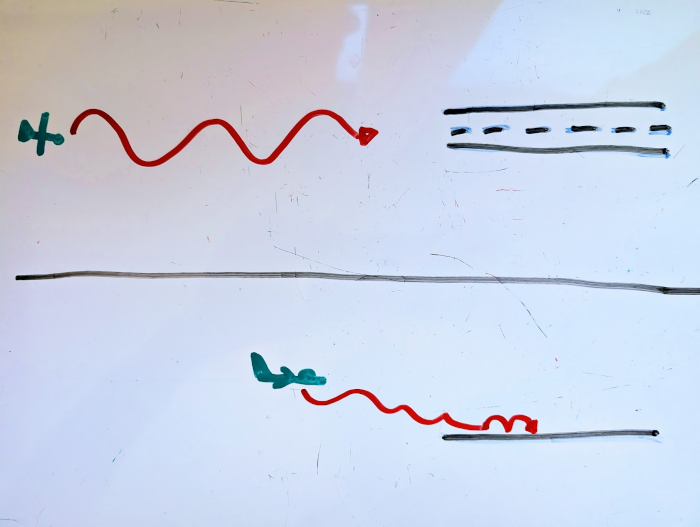

Maybe software is the solution! I learned about evdev (and a Python library), which lets me read and write input events on Linux. With many iterations in between, long story short, I ended up with a solution: injected Javascript in GeoFS allows me to transform the input ranges from the two joystick axes and the pedal axis, respectively, before passing the transformed input to GeoFS in order to affect ailerons, elevator, and the rudder. I used a polynomial, using p=3 for the pedal, and p=2 for the lateral and vertical axes. Omitting the maths to deal with the input not being centered around zero, omitting the dead zone to avoid spurious input, omitting the sign flips needed when p is even, it essentially boils down to a simple polynomial:

The results were satisfying. When providing small inputs on the physical joystick or the physical rudder pedal, the outputs were disproportionally small, allowing for finer control of the plane—much easier to keep it centered on the runway during take-off, for instance. When providing larger inputs, the plane would respond without giving the controls a sluggish feeling. Nice.

Finally: to every action, there is always opposed an equal reaction. Newton’s law also applies to my rotating office chair. When I applied some action to the joystick, my office chair would rotate. Not great. For this, I cut out a few caster stoppers with the laser cutter. These caster stoppers were ugly but effective: the office chair stopped rotating. No, I still do not have a seat belt.

In summary, what really helped to move from crash-landing the plane in GeoFS nearly every single time to decent-looking landings most of the time:

- getting advice from the flying instructors of the Internet

- adjusting perception and mental models

- joystick and pedal instead of keyboard for controlling pitch, roll, yaw

- throttle lever instead of keyboard for controlling thrust

- software-defined curves to yield very small responses to small corrections

- pilots don’t sit on rotating office chairs, probably for a reason

- practice, practice, practice